Uzbekistan Part V - Fergana Valley

Feeling much more energetic and on the mend after commencing a course of antibiotics, we were ready to hit the road again in the opposite direction, this time east of Tashkent to Fergana Valley, the last leg of our Uzbek roadtrip.

All the while as we drove through the Fergana Valley and up and over mountains, Marat’s car stereo provided just the right thematic background to the scenery. I wanted to hear what the country’s music sounded like. At first Marat put on American country music, which he is fond of. No, no, I said. Your country’s music! So, we listened to contemporary and traditional tunes, some sung in Russian, others in Uzbek and still others in Tajik.

Roadside stalls along the way and on the return once again proved to be interesting stops, especially to us foreigners. A major military checkpoint meant handing our passports to our driver who then passed them over for processing. This side of the regional border, whilst more conservative, has seen political unrest and people are screened entering and leaving, although it’s pretty safe for tourists.

Fergana Valley is very much a rural-based economy. In the irrigated fields are fruit trees, tobacco fields, wheat, corn and massive cotton plantations. Cotton is one of Uzbekistan’s main industries, a water-thirsty plant that is irrigated by canals that channel water from the tributaries of the Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya rivers (the Oxus and Jaxartes rivers as they were known in ancient Greek).

Margilon looks like a Russian town in the grid-like layout of its streets. There are wide boulevards lined with shady trees, there are parks and gardens, and the town has a green lushness to it.

A visit to a small silk factory was a fascinating insight into silk production. This factory is renowned for its quality silks, one of the main reasons for visiting Fergana. I wanted to see where a part of ancient China’s secret knowledge of silk had spread along the Silk Route. An intriguing story about how the mystery of silk making reached the West goes that a couple of monks heading back to the Byzantine emperor hid silkworm eggs in their hollowed staffs (or should that be staves?).

The silk at this factory is produced by two methods – the traditional way by hand as has been done for centuries and by old mechanical looms. Nowhere in the factory did we see electricity used in its production bar the fluorescent lighting in the workrooms. Making up a group of only the two of us, we were led around to where the silkworm cocoons are boiled and the white silk spun on old wooden spinning wheels. We watched a dyer hand-dyeing the skeins of silk in natural dyes extracted from fruits, vegetables and natural pigments. His hands were stained that morning from indigo that has travelled across the border from Afghanistan, a big producer of this dye. There were rooms of young male designers kneeling on the floor sketching designs directly onto the silk before the dyeing process, and a large factory space of wooden looms where men and women wove the coloured silk into brilliantly patterned fabrics. The weavers each held a bottle of milky fluid which they’d occasionally sip from and then skilfully spray this liquid from their mouths in perfect arcs over the fabric as it was being woven. Of course, the best part was walking into the shop of fabrics, clothing, scarves and pashminas in rainbow colours too gorgeous to resist.

Driving past a local bakery made for an impromptu stop to watch a local baker at work. Marat was aware of our curiosity and interest in the local breads and this turned out to be a spontaneous opportunity to see first-hand. Within the space of two tiny rooms, the baker and his 2 assistants were churning out 1500 loaves of flatbread a day. One would weigh each batch of dough, the other to shape it into a flat round and stamp its centre, and the baker glazed and sprinkled each with caraway and sesame seeds before flattening each bread in rows onto the hot interior walls of a domed oven for baking. Since the Soviets left, Marat explained, the people are reverting to their traditional ways and foods. The big Soviet bread factories are not as popular anymore. Seems like Uzbeks are discovering and exploring their national identity.

Driving past a local bakery made for an impromptu stop to watch a local baker at work. Marat was aware of our curiosity and interest in the local breads and this turned out to be a spontaneous opportunity to see first-hand. Within the space of two tiny rooms, the baker and his 2 assistants were churning out 1500 loaves of flatbread a day. One would weigh each batch of dough, the other to shape it into a flat round and stamp its centre, and the baker glazed and sprinkled each with caraway and sesame seeds before flattening each bread in rows onto the hot interior walls of a domed oven for baking. Since the Soviets left, Marat explained, the people are reverting to their traditional ways and foods. The big Soviet bread factories are not as popular anymore. Seems like Uzbeks are discovering and exploring their national identity.

Leaving the Fergana Valley and heading back to Tashkent via the city of Kokand, before jetting off for Europe, had us reflecting on our 2 week stay in this beguiling country. From lush valleys to stark deserts, craggy mountains, mudbaked villages and modern towns, it’s a land of contrasts. From a palette of browns and earthen colours to the vibrant rainbow colours found on silks, ceramics, embroideries, the tapchans of teahouses and worn by its women.

Leaving the Fergana Valley and heading back to Tashkent via the city of Kokand, before jetting off for Europe, had us reflecting on our 2 week stay in this beguiling country. From lush valleys to stark deserts, craggy mountains, mudbaked villages and modern towns, it’s a land of contrasts. From a palette of browns and earthen colours to the vibrant rainbow colours found on silks, ceramics, embroideries, the tapchans of teahouses and worn by its women.

|

| Stopping off to buy a melon |

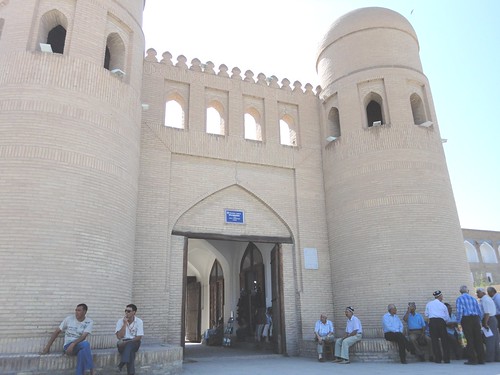

Our journey would take us up and over mountains, through the Kamchik mountain pass and to Fergana Valley’s silk production town of Margilon and to Rishton, renowned for its ceramics. Whilst not big on the 4 M’s (mosques, minarets, madrassas and mausoleums) this region is big on Markets.

|

| Through the Kamchik Pass to Fergana Valley |

|

| Roadside produce |

All the while as we drove through the Fergana Valley and up and over mountains, Marat’s car stereo provided just the right thematic background to the scenery. I wanted to hear what the country’s music sounded like. At first Marat put on American country music, which he is fond of. No, no, I said. Your country’s music! So, we listened to contemporary and traditional tunes, some sung in Russian, others in Uzbek and still others in Tajik.

Roadside stalls along the way and on the return once again proved to be interesting stops, especially to us foreigners. A major military checkpoint meant handing our passports to our driver who then passed them over for processing. This side of the regional border, whilst more conservative, has seen political unrest and people are screened entering and leaving, although it’s pretty safe for tourists.

|

| Max and Marat in cotton fields Cotton blossom below (or should that be a cotton bud?) |

Margilon looks like a Russian town in the grid-like layout of its streets. There are wide boulevards lined with shady trees, there are parks and gardens, and the town has a green lushness to it.

Here we were shown around several bazaars, bustling places all of them with gold-toothed smiling vendors, many asking to have their photo taken and wanting to know where we were from. Some offered us samples of crystallised sugar, fruit or a handful of peanuts. We passed by stalls of fruits and vegetables, breads, sacks of nuts and spices, crisp sweet pastries lightly sprinkled with caraway seeds stacked high in little piles, past the sour smell of the dairy section where homemade yoghurt filled plastic Coke bottles and mounds of soft farm cheese that looked like cottage cheese lay in tubs or spread out on plastic sheets.

A weekend bazaar on the outskirts of town had us haggling over a $5 ‘brand label’ cotton T-shirt amongst the rows and rows of clothing stalls. This outdoor market was also THE place to come and buy spare auto parts, kitchen sinks, plumbing fixtures, tools, shoes, ceramics and furniture. It looked like a monster Swapmeet.

|

| Beautifully-patterned flatbreads |

A visit to a small silk factory was a fascinating insight into silk production. This factory is renowned for its quality silks, one of the main reasons for visiting Fergana. I wanted to see where a part of ancient China’s secret knowledge of silk had spread along the Silk Route. An intriguing story about how the mystery of silk making reached the West goes that a couple of monks heading back to the Byzantine emperor hid silkworm eggs in their hollowed staffs (or should that be staves?).

|

| Silk weaver at loom |

The silk at this factory is produced by two methods – the traditional way by hand as has been done for centuries and by old mechanical looms. Nowhere in the factory did we see electricity used in its production bar the fluorescent lighting in the workrooms. Making up a group of only the two of us, we were led around to where the silkworm cocoons are boiled and the white silk spun on old wooden spinning wheels. We watched a dyer hand-dyeing the skeins of silk in natural dyes extracted from fruits, vegetables and natural pigments. His hands were stained that morning from indigo that has travelled across the border from Afghanistan, a big producer of this dye. There were rooms of young male designers kneeling on the floor sketching designs directly onto the silk before the dyeing process, and a large factory space of wooden looms where men and women wove the coloured silk into brilliantly patterned fabrics. The weavers each held a bottle of milky fluid which they’d occasionally sip from and then skilfully spray this liquid from their mouths in perfect arcs over the fabric as it was being woven. Of course, the best part was walking into the shop of fabrics, clothing, scarves and pashminas in rainbow colours too gorgeous to resist.

Driving past a local bakery made for an impromptu stop to watch a local baker at work. Marat was aware of our curiosity and interest in the local breads and this turned out to be a spontaneous opportunity to see first-hand. Within the space of two tiny rooms, the baker and his 2 assistants were churning out 1500 loaves of flatbread a day. One would weigh each batch of dough, the other to shape it into a flat round and stamp its centre, and the baker glazed and sprinkled each with caraway and sesame seeds before flattening each bread in rows onto the hot interior walls of a domed oven for baking. Since the Soviets left, Marat explained, the people are reverting to their traditional ways and foods. The big Soviet bread factories are not as popular anymore. Seems like Uzbeks are discovering and exploring their national identity.

Driving past a local bakery made for an impromptu stop to watch a local baker at work. Marat was aware of our curiosity and interest in the local breads and this turned out to be a spontaneous opportunity to see first-hand. Within the space of two tiny rooms, the baker and his 2 assistants were churning out 1500 loaves of flatbread a day. One would weigh each batch of dough, the other to shape it into a flat round and stamp its centre, and the baker glazed and sprinkled each with caraway and sesame seeds before flattening each bread in rows onto the hot interior walls of a domed oven for baking. Since the Soviets left, Marat explained, the people are reverting to their traditional ways and foods. The big Soviet bread factories are not as popular anymore. Seems like Uzbeks are discovering and exploring their national identity.

Rishton was a ceramics stop to view the works of the internationally-recognised master ceramist Ristam Usmanov. Although not at home that day, his wife welcomed us through the massive wood carved doors of their property, through his private collection of antique ceramics, and out to his studio and workshops. Only the purest of clay that is derived from a small region nearby and the purest of water is used in his creations – no other ingredients apart from the natural pigments and dyes in his artwork.

Leaving the Fergana Valley and heading back to Tashkent via the city of Kokand, before jetting off for Europe, had us reflecting on our 2 week stay in this beguiling country. From lush valleys to stark deserts, craggy mountains, mudbaked villages and modern towns, it’s a land of contrasts. From a palette of browns and earthen colours to the vibrant rainbow colours found on silks, ceramics, embroideries, the tapchans of teahouses and worn by its women.

Leaving the Fergana Valley and heading back to Tashkent via the city of Kokand, before jetting off for Europe, had us reflecting on our 2 week stay in this beguiling country. From lush valleys to stark deserts, craggy mountains, mudbaked villages and modern towns, it’s a land of contrasts. From a palette of browns and earthen colours to the vibrant rainbow colours found on silks, ceramics, embroideries, the tapchans of teahouses and worn by its women.

Contrary to what our guidebook and blogsites stated about its capital, Tashkent, about police shaking down tourists for money especially in metro stations, we didn’t encounter any trouble. It’s been refreshing to find a people so open, who like to meet foreigners. We’ve learnt a few Uzbek words in return “bir, ikki, uch , sirrrr” (1, 2, 3, Uzbek cheese!”).

Our journey has been a discovery of hospitable peoples along the way, of a land adorned with captivating architecture and beautiful tiles, of a country with an enthralling history and a fresh identity being rediscovered. Appearances are a blend of Asian, Mongolian and Western features. A confluence of cultures, their country’s history and legacy displays on its people’s faces.

As Marat drove us into Tashkent for the last time, tears sprung to my eyes as I realised that we were nearing the end of a dream visiting this beautiful and exotic land. What an incredible feeling and adventure it’s been to have had the chance to imprint our footsteps on a small part of the huge network of roadways once travelled by traders and camel caravans on their torturous journey along the Silk Route.

|

|

| Roadside breadsellers - all wanting their produce to be photographed |

Hi, I'm Eva - world traveller, cultural explorer and experience seeker. Together with my husband Max, we've been globetrotting for over 20 years.

Hi, I'm Eva - world traveller, cultural explorer and experience seeker. Together with my husband Max, we've been globetrotting for over 20 years.

0 comments: